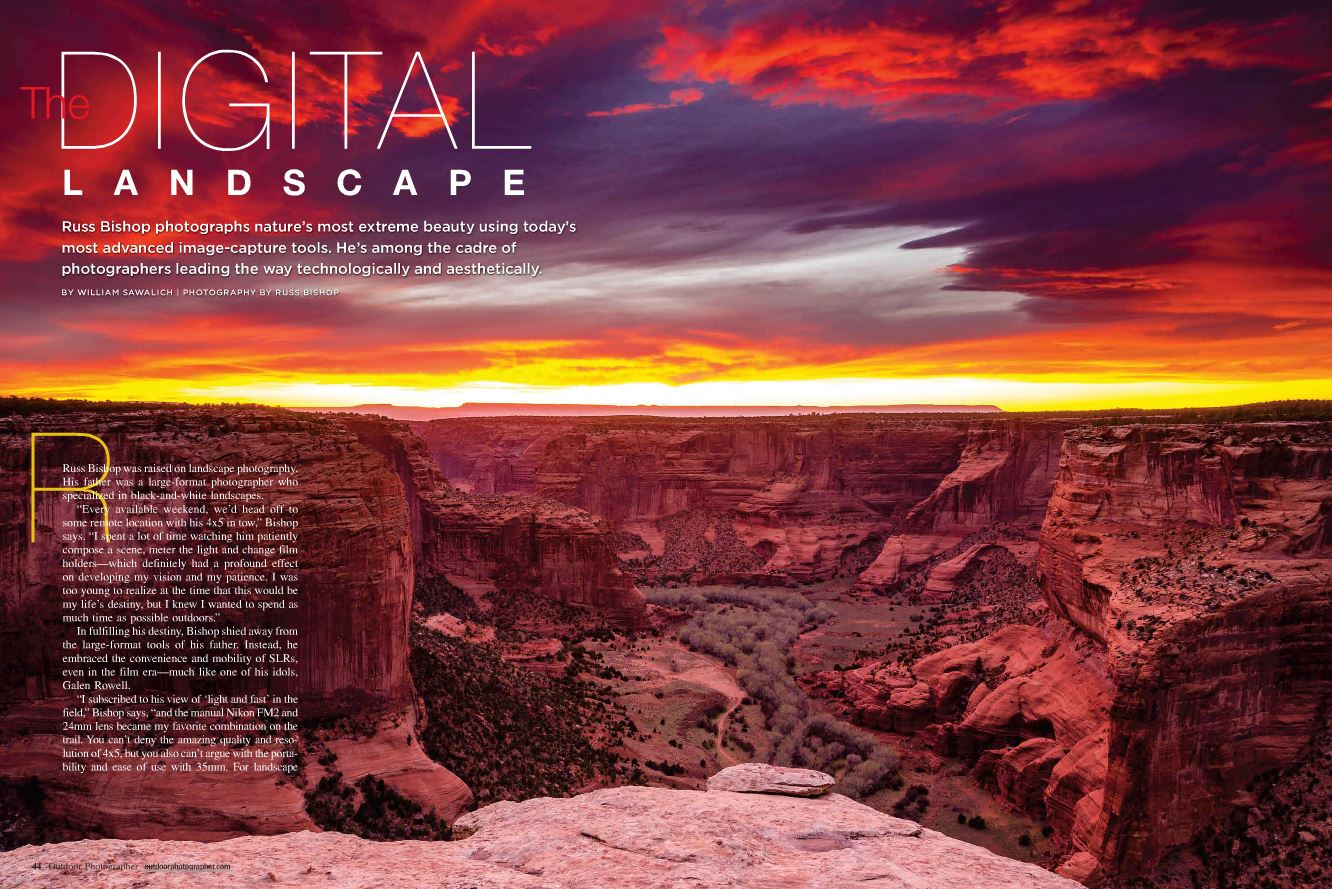

How many times have you arrived at a scene, anxious and ready for the show to begin only to find that Mother Nature had other plans. The light is far from spectacular, and your perfect image just faded before your eyes (or sensor) ever had a chance to capture it. Typical? Yes, but there’s just one problem. There is no such thing as bad light!

The issue is more with perception than the reality before you. Sure it requires a change of plan, but photography in its simplest form is painting with light (any light) and in that context, it’s all good. Learning to work with a variety of light will expand your visual toolkit and result in more satisfying and dynamic landscape images.

Big puffy clouds will always add drama to a landscape. But what if the sky is a sea of blue with nothing to balance the frame except an intense sun in the wrong location? Use a small aperture with that wide-angle lens and create a dynamic sunstar. This is a great opportunity for visual storytelling. Include a silhouette of a person involved in an activity or a defining landform and you’ve just turned that bad light into a compelling image.

But now you say the sky is completely overcast with no direct light anywhere? This is the perfect time to point your lens to the finer details below the horizon or at your feet. In this case, the sky is simulating a giant studio softbox with broad even lighting and no shadows – perfect for macro shots and isolating elements of the scene with a telephoto. That drab looking light will actually enhance the colors of flowers and trees, and combined with a slow shutter speed it will turn water into silk.

So the next time you’re met with less than ideal conditions, think twice before packing it in. Taking a different approach to the weather and thinking outside the box could be the only difference between creating some powerful imagery or nothing at all.

©Russ Bishop/All Rights Reserved